Shrinking the Trie for the Wire

Part 5 demonstrates a trie-powered autocomplete component that searches entirely in the browser. No debouncing, no server round-trips — just a trie and instant results.

But I glossed over an important question: how does the trie data get to the browser?

If your dataset is 50,000 entries with popularity scores, someone has to download that data. JSON is the obvious format — but it’s not particularly compact. Every entry repeats {"text":" and ","score": — that’s 19 bytes of structural overhead per entry.

What if we could send the trie itself instead? Serialize the radix tree into a compact format, eliminate the redundant JSON syntax, and ship a smaller payload.

That was the hypothesis. Then I measured it. The answer was surprising - it’s not better!

The Hypothesis: Serialize the Trie

A radix trie already compresses prefixes. “San Francisco”, “San Diego”, and “San Jose” share a “San " edge — stored once, not three times. Serializing this structure should yield something smaller than a flat JSON array where every entry is independent.

I created a text-based packed format:

PTRIE:2:CI:S

0.95,0.90,0.85,0.80

---

-|San >1|Los >2

!| Francisco>3|Diego>4|Jose>5

!|Angeles>6

!

!

!

!

Edge labels preserve original case. Texts are reconstructed by walking from root to terminal nodes — no separate text section needed. Scores are stored once in a compact comma-separated table. The format eliminates all of JSON’s per-entry syntax overhead.

On paper, this should win.

The Experiment

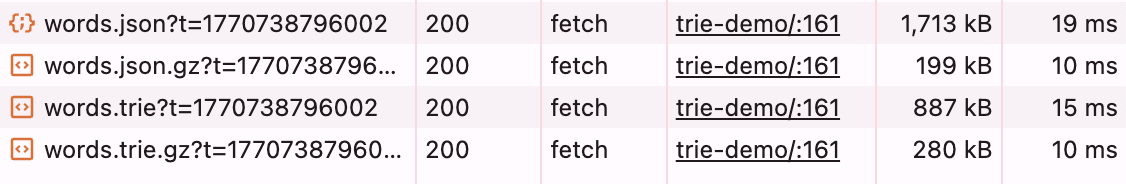

I took the ~200K words from the macOS system dictionary, assigned sequential frequency scores, and created a few sample reasonable encodings. Then I compressed each one with gzip and Brotli to simulate what an actual web server would deliver.

Here are the results:

| Format | Raw | Gzip | Brotli |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain word list (no scores) | 506 KB | 158 KB | 136 KB |

| JSON string array (no scores) | 604 KB | 162 KB | 138 KB |

| JSON entries [{text,score}] | 1,672 KB | 195 KB | 147 KB |

| Text + score line | 750 KB | 159 KB | 137 KB |

| Packed trie v2 (text) | 866 KB | 273 KB | 229 KB |

| Packed trie v2 (no scores) | 624 KB | 272 KB | 228 KB |

| Binary trie (with scores) | 574 KB | 280 KB | 238 KB |

| Binary trie (no scores) | 477 KB | 279 KB | 236 KB |

The packed trie is 48% smaller than JSON in raw form. But after compression, every trie format is larger than every flat format. The 1,672 KB JSON that looks so wasteful? Gzip cuts it to 195 KB. The 866 KB packed trie? Gzip only gets it to 273 KB. Brotli widens the gap further.

I tried binary encoding. I tried stripping scores. The trie formats consistently compressed worse than flat text.

Why Gzip Wins

So why is the trie format worse than the flat text format?

Gzip (and Brotli, and zstd) use LZ77 — a sliding-window algorithm that finds repeated byte sequences and replaces them with back-references. It doesn’t understand data structures. It sees bytes.

JSON is repetitive in a way gzip loves. The string {"text":" appears 50,000 times — gzip encodes it once and back-references the other 49,999 occurrences. The string ","score": — same thing. After gzip strips all that repetitive syntax, what remains is mostly the unique word fragments and score digits. That’s about 160 KB of incompressible content.

A trie is repetitive in a way gzip can’t exploit. The trie eliminates prefix redundancy structurally: “San " is stored once as an edge label instead of appearing in each entry. But the serialized format replaces that redundancy with child-pointer references — base-36 node indices like >1a3, >2f, >a9. These indices are essentially random numbers. They point to wherever the child node happened to land in the BFS ordering.

Random data doesn’t compress.

The trie trades one form of redundancy (repeated prefixes) for another form of overhead (structural pointers). Gzip could already handle the repeated prefixes — it’s exactly what LZ77 was designed for. The pointers are new overhead that gzip can’t remove.

Here’s the fundamental insight: the trie and gzip are competing to eliminate the same redundancy. When you apply both, they don’t stack — the trie removes patterns that gzip would have caught anyway, and adds structural overhead that gzip can’t touch.

What About the Flat Formats?

Look at the “Text + score line” format: just words separated by newlines, then a --- separator, then comma-separated scores. Raw, it’s 750 KB. After gzip: 159 KB. That’s smaller than gzipped JSON entries (195 KB), because there’s no per-entry syntax at all.

But here’s the kicker: the plain word list (506 KB raw, 158 KB gzipped) is almost the same compressed size as the text-with-scores format (750 KB raw, 159 KB gzipped). The scores added 244 KB of raw data but only 1 KB after gzip. Sequential scores are massively compressible because they follow a predictable pattern.

What about random scores? I tested that too, on the hypothesis that random scores would be harder to compress:

| Format | Gzip (sequential scores) | Gzip (random scores) |

|---|---|---|

| JSON entries | 195 KB | 268 KB |

| Packed trie | 273 KB | 332 KB |

Random scores hurt both formats, but hurt JSON more (+73 KB vs +59 KB for the trie). Scores scattered across 50,000 JSON objects are harder to compress than scores in a single comma-separated line. This is the one place the trie format’s structure helps — but not enough to close the gap.

The Right Tool for Each Job

The trie is the wrong data structure for wire transfer. It’s the right data structure for search.

The mistake was conflating two different problems:

- Transfer: get the data from server to client as small as possible

- Search: once in memory, find prefix matches as fast as possible

These problems have different optimal solutions. For transfer, the answer is already solved: send flat text, let HTTP compression handle it. For search, build the trie in the browser after the data arrives.

Here’s what the practical architecture looks like:

Server: sorted word list + scores

↓ HTTP (gzip/brotli: ~150 KB for 50K entries)

Browser: receive flat data

↓ Build trie (fast — ~50ms for 50K entries)

Browser: trie in memory, ready for prefix search

The TrieAutocomplete component already supports this — the entries and items props accept flat data and build the trie client-side via useMemo:

<TrieAutocomplete

entries={[

{ text: 'New York', score: 0.95 },

{ text: 'New Orleans', score: 0.90 },

// ... loaded from any API

]}

placeholder="Search cities..."

/>

The trie construction happens once. After that, every keystroke is O(L) prefix search — no scanning, no filtering, no debounce needed.

When Would a Custom Wire Format Win?

Our experiment used English dictionary words — short, with moderate prefix sharing. Are there datasets where a packed trie would beat gzipped JSON?

I think the answer is: rarely, for transfer. The fundamental issue — random pointers defeating compression — applies regardless of the data. But a custom format could win in a different dimension:

Parse time. JSON.parse() on a 1.7 MB string creates 50,000 JavaScript objects on the heap. A packed trie format could be parsed into a more memory-efficient structure directly, avoiding the intermediate array. For very large datasets (100K+ entries), this could reduce memory pressure and GC pauses.

Streaming. A trie format could be designed for incremental parsing — start returning search results before the entire file is downloaded. JSON arrays don’t support this without custom streaming parsers.

For most autocomplete use cases, though, JSON is the right answer. The dataset is small enough (10K–50K entries, ~150–250 KB gzipped) that parse time is negligible and streaming is unnecessary.

What I Learned

I built three different trie serialization formats: a text-based packed format, a binary encoding, and a radix tree variant with no separate text section. All three lost to gzipped JSON for wire transfer.

The lesson is about understanding your compression stack:

- Don’t compete with gzip. If your custom format is eliminating the same redundancy that gzip eliminates, you’re adding complexity for no gain.

- Separate structure from transfer. The trie’s value is in-memory search performance, not wire efficiency. These are different problems.

- Measure everything. The hypothesis was plausible. The format was reasonable. And it was wrong.

The trie started this series as a simple tree for storing strings. We visualized it, scanned text with it, broadcast it across a Spark cluster, and built a React autocomplete with it. Here, we tried to make it a wire format — and learned that some problems are already solved.

Sometimes the best optimization is knowing when to stop.

The Series So Far

- What Is a Trie? — The data structure, from intuition to implementation

- Building an Interactive Trie Visualizer with D3 — How the animated visualization works

- Scanning Text with a Trie — Multi-pattern matching, word boundaries, overlap resolution

- Broadcasting a Trie in Spark — The distributed computation pattern

- Building a Trie-Powered Autocomplete with React — The React component

- Shrinking the Trie for the Wire — You are here

A trie that started as a tree for storing strings became a visualization, a text scanner, a distributed broadcast, and a React UI component. The last experiment — trying to compress it for the wire — taught us something about the limits of custom formats and the quiet competence of general-purpose compression.